VTXL: the 2025 edish

With the foundation set, let’s jump to my most recent run at the course. This is a long winded blow-by-blow of how I took the VTXL FKT.

There’s a bit of reverse engineering involved in deciding the best start time. If history is any indication, the ballpark estimated time is “about 22 hours”. One of the biggest considerations in my mind is that Stratton Mountain looms large towards the end of the ride, which is a nine-mile singletrack climb with a plateau over the top followed by a screaming fast, swooping ten-mile gravel road descent. “Singletrack” is a tiny bit of an exaggeration; while it is technically singletrack, but it’s also pretty much a literally straight forward 7% climb. That said, there are thousands of baby head rocks scattered on the trail and depending on how much maintenance has been done lately, the narrow path can also be hidden under waist-high grass. So while you can definitely ride it in the middle of the night, knowing that once you start you’re committing to a minimum hour and a half session, it’s much more pleasant to approach that in the light of day.

There is a trail there, as indicated by Tim Johnson, 2023. This is the smooth “highway” section; trust me it gets much chunkier.

Bigger picture, I generally assume that overall speeds are faster in daylight as opposed to riding courtesy of a handlebar light, so maximizing daytime and minimizing nighttime is the goal. I therefore picked a 9pm start time, which would allow me to eek out every iota of sunlight the following day. Sunset is just shy of 7:30pm this time of the year, but there’s so much time in the woods that by the time 7pm rolls around, you’re pretty much reliant on supplemental light.

I live in the world of content creation, so when Zipp and Rene Herse expressed interest in creating a video of this adventure I was stoked. Therefore by bikepacking rules, from the very get-go it’s considered a supported FKT. In the month prior to this ride, I came a whisker’s distance from doing the ride totally solo — self-supported, no video, just send it. But for reasons I can’t really put a finger on, I got cold feet just 30 minutes shy of departure (in the car, that is, not 30 minutes short of the first pedal stroke) and kicked the can down the road, presumably until 2026.

Can we talk for a minute about how point to point rides are the absolute best?! There’s a unique sense of accomplishment that comes with “wow, I ended up all the way over here instead of way back there”. Given the scope of a VTXL, the logistics of getting to two very remote corners of the state are very challenging, making the entire ride that much more special.

The convenience of this being a supported ride is therefore hard to ignore. That is, having a ride to the start and an immediate pick-up from the finish is extremely helpful. My good friend Chris Milliman and I have done plenty of projects together starting back in 2011 (gasp), and it was actually his nudging that got me onboard with the idea of doing the VTXL this late into the season rather than pushing until next year. It also takes a certain level of knuckleheadness to voluntarily stay awake all night documenting this type 2 fun and Chris was totally game. If he was up for it, so was I, as was our friend and Chris’ often assistant Tim, “audio and drone guy” extraordinaire.

After a full day of getting the kids off to school, proactively catching up on work knowing that I’ll be offline for the next two plus day, doing all the last minute packing and prep, I finally pack up and first set off at 4:30pm on a 75 minute drive to meet up with Chris and Tim, where I dropped my car, then hop in their rented minivan and was off on additional two hour drive.

I was once upon a time teammates with Carlos Sastre. Maybe it’s the Spanish siesta lifestyle, maybe just his innate talent, but to this day his ability to close his eyes and be asleep impresses me. From 1-3pm on departure day when I was tossing and turning in bed trying to log a nap, and from 6-8pm when we were driving to the start point of Canaan, VT and my eyes were closed but I wasn’t asleep, I wished I had whatever Carlos possessed that allowed him to sleep on cue. Just a few minutes of a last minute nap was all I really wanted — something I’d especially rue not having the middle of the next afternoon.

We drove into Canaan at 8:30pm. Arriving in normal clothes, I then detonated the controlled explosion of clothing and gear in the van in an effort to start pedaling. It was a muggy 50 degrees at the start, but temperatures overnight were forecasted to be in the high 30s with daytime highs the next day in the upper 70s. That’s a considerable temperature delta for which I want to be prepared with leg warmers, multiple pairs of gloves, warmer gloves, neckgaiter, jackets, vests, shoe covers, etc. Plus there’s the pocket packing process of food, phone, earbuds, headlamp, and so forth, which all sounds easy, but still takes more time than one would normally expect. Nearly on time a bit after 9pm, after some initial scene-setting words to the camera, I was off.

It’s a bit of a catch-22 having this a “supported” ride. It would make this adventure waaaay easier if I just called the van my support vehicle and took a page out of pro road racing. That is, ride with the weight of just one bottle, pack my pockets with a single UnTapped pack or two, and grab or drop clothes as needed when I raise my arm to ask the van to come up to me.

But there’s the principle of this being a FKT and my desire to be largely self supported. Yes, I said largely, not entirely. Ultimately I plan to see the van every handful of hours. Furthermore, Chris and Tim are more or less flies on the wall. They’re documenting and observing, but they’re also driving a minivan on a mix of municipal gravel roads and ancient, rugged logging roads, so they have to leapfrog most of the 300 mile route as opposed to just driving behind. So even if I wanted them on my tail, I might go three or four hours without them being anywhere nearby.

There’s not a single cloud in the sky and now well dressed for the impending cold, I start pedaling the two “neutral” paved miles before a left turn onto Judd Road. The gravel begins, the climbing begins, and the VTXL has officially starts.

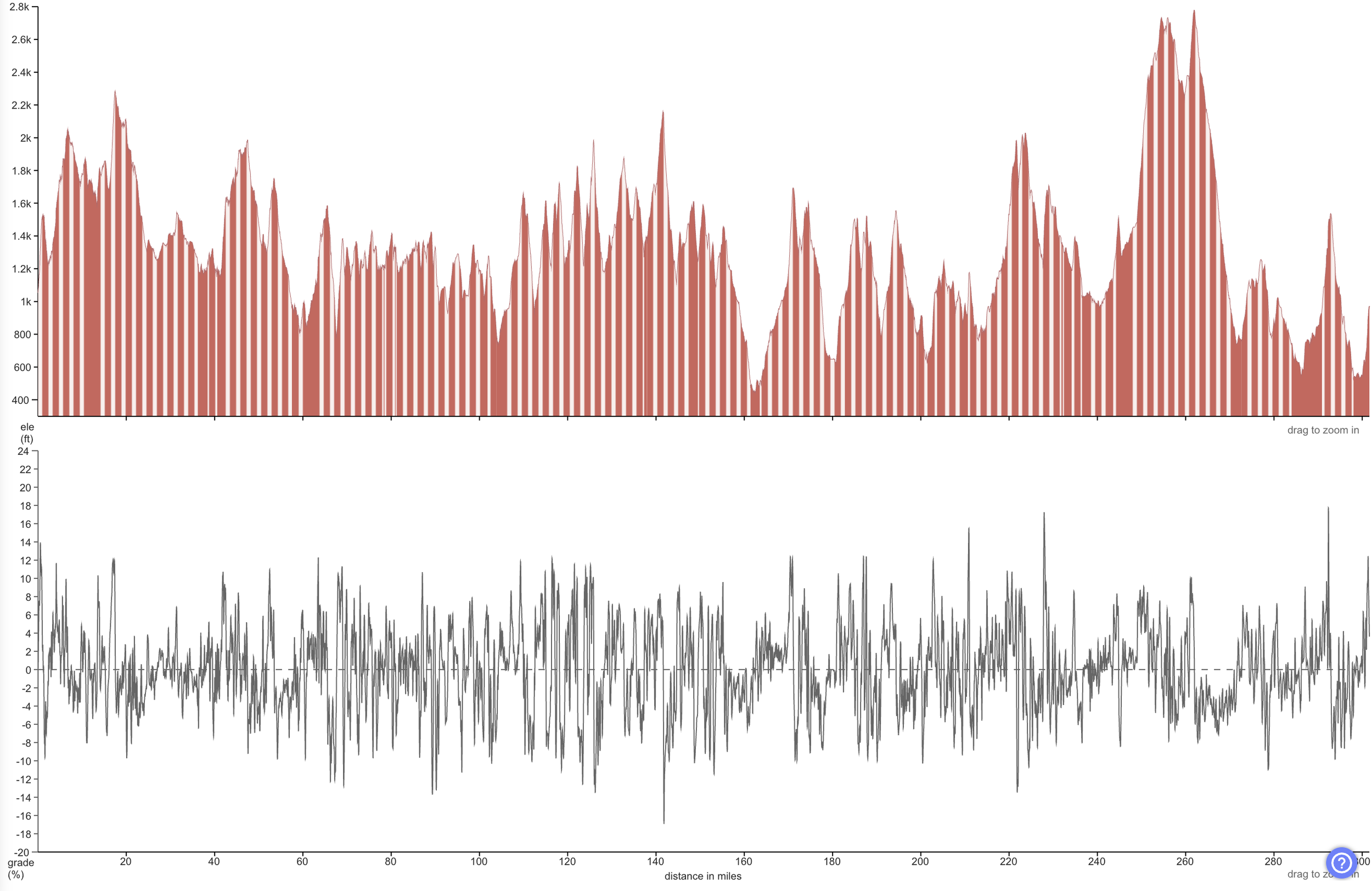

It’s impossible not to be eager and excited at this point in the ride. I feel a giddy punch-drunk feeling of energy as I’m setting off on this enormous adventure already deep into the evening. With two kids under six-years old at home, if parenting has taught me anything, it’s to log quality sleep I go to bed early… so I’m usually fast asleep at this time of the day! I keep that energy in check, however, because even though I can look at an elevation profile and literally count the number of climbs or we can tally the elevation to be conquered (just shy of 33,000 feet), the climbs are simply incessant.

The top is the elevation profile and the bottom is the gradient, so anytime the black line goes over the center 0 dotted line, we’re going uphill. If anything Ride with GPS, used here, underestimates gradient as a result of averaging, so there are dozens of climbs that tip into the high teens and mid-20% grade.

I have a lengthy playlist of music and podcasts to help pass the time, but I’m so entranced by riding at night I don’t want to even tune into supplemental sound. Sight is limited to what my handlebar light casts in front of me so I need to double down on paying attention what’s in front of me. In other words, I see half as well so I need to pay twice as much attention.

The opening hours tick by quickly. These are a series of interwoven snowmobile roads and trips up and down enormous powerline hills. The dim glow of my GPS keeps me on track with most of my attention on the road ahead. On a few occasions, I don’t remember if it’s two or three, but I encounter washed out bridges. These are the remanent of the once-in-100-year storms that ravaged the state three times in the past decade.

Maybe three hours into the ride, I cruise into the town of Island Pond, which is fast asleep. I sit down on the cold pavement to dawn my booties — the first time of the season — and put on my winter gloves. Once back up and moving, I’m very happy to have them. It’s already cold and having looked at the hourly forecast, the coldest stretch is still hours away right at dawn.

Plugging along, the 3:30-5:30am window is the toughest of the overnight stretch. I’m now 8 hours into the ride, which is a massive ride under by any other metric besides today, and the tunnel vision of only seeing the circle ahead of me provided by a powerful headlight is tiring. THIS is why I wanted to postpone the ride until 2026: longer days, warmer nights! I’m not regretting the decision to take on this challenge right now, but it’s sure presenting itself as difficult. The sun can’t come soon enough.

The lowest temperature I see on my handlebar computer is 37 right at sunrise. I’m about nine hours and 130 miles in, which is equal parts daunting and motivating to know I’m nearly halfway through… and with a full day of sunlight ahead, it’s only 6am.

I’ve ridden my bike all over Vermont, of course. There are a whole series of zones designed in my mind as a result of all the riding I’ve done in each portion. The northeast part of the state is called the Northeast Kingdom. I designat that into the three zones “right up by Canada”, next is the “Burke and Kingdom Trails area”, then later on “near where Ian Boswell lives”. The NEK segues to the eastern part of the state all around Tunbridge, for which the first word that comes to mind associated to this region is “hilly”. AF. From there you drop into Sharon, which is 160 miles in to the ride, so for all intents and purposes, as well as courtesy of the enormous descent to the White River, it’s the “halfway point”. From here you’re riding (uphill forever) to Woodstock which is “horse country and stately estates”. It’s a posh and beautiful part of Vermont.

It’s this next area, between Woodstock to Londonderry, that lives in a blur in my mind. See, there are plenty of times into the lead-up of something big that you confidently tell yourself, “pshh, I can do so-and-so for so-and-so period of time.” For example, I can stay awake for 48 hours. Or, I can ride a bike for 24 hours, no problem! It’s in the heat of the moment where push comes to shove and these physical challenges become mental tests as much as anything.

It’s admittedly odd to say mind over matter, to mentally will your body to make a physical action when all you really want to do is lie down and sleep. But that’s simply what it is, mental more than physical.

Maybe this is a blur because the Woodstock to Londonderry zone is a place I’ve spent the least amount of time. Maybe it’s because I’m 14,000 kilojoules into the ride with plenty more still ahead. Maybe it’s because I haven’t slept in 32 hours. Maybe it’s because I was buoyed with my initial 16mph average, but then I saw my average speed steadily drop to 14mph, which was well off the FKT pace. WHATEVER THE CASE, all I want to do right here is quit.

That’s another odd thing to comprehend, especially in hindsight. Because I was out there voluntarily. It’s not as though I was in physical danger. The sun is out and the day is warm (…finally. I failed to mention it continued to be a very very chilly morning, so it wasn’t until about noon that I finally took off my gloves, leg warmers, and swapped to a short sleeve jersey). So in retrospect it’s easy to say, “yeah bud, just keep plugging along!” but in those moments, it’s cripplingly difficult to will yourself to a single pedal stroke, let alone the tens of thousands required to make it to the finish. Just keep going.

I frankly don’t know how I got a second wind, likely chugging what ultimately ends up being more than a half gallon of maple syrup, but the next zone of Londonderry to Stratton Mountain, and then the entire drag from the high point of Stratton Mountain to the finish, I found some pep.

The penultimate climb over Mount Anthony is a doozy and even though I can look at a map and tell you it’s exactly 8.1 miles from the peak, down the other side, then up the final “why are we ending on such a steep climb?!” to the Massachusetts' border and therefore the finish line, it felt like three times that.

To anyone who’s ridden this route or is familiar with the area, you’ll chuckle when I say there isn’t much fanfare at the finish. There’s a large granite pillar with a couple houses on either side and not much else. An elderly man was drinking a beer and listening to music in his garage there around 7pm when I reached the border and asked what was going on. “Why are there so many bikers riding through here today?” It’s such a sleepy part of the state, that the three cyclists he saw over the course of the day, presumably at least some finishing the VTXL, constituted something different from the norm.

Amid this lack of celebration, even more into my punch-drunk stupor than 300 miles previously, we crammed into the minivan and drove two and a half hours back to our original meeting point and my van. The clock said 11pm, so I’m now logging my 42nd hour of being awake and I promptly pass out. (In the bed in the back of the van, that is, safe and sound.)

My alarm chirps awake at 5am so that I can get home and help get the kids off to school just two hours later. Not too much rest for the weary.